HealthByte 003

This week: Decoding coffee's genetic past, phage insights from cholera infections, and airborne biodiversity detection.

Welcome to HealthByte, your curated source for the latest breakthroughs in health and life sciences!

Bytes of Research

1. The genome and population genomics of allopolyploid Coffea arabica reveal the diversification history of modern coffee cultivars

(Nature Genetics)

TL;DR: The study examined the genetic makeup of Coffea arabica and its parent species, highlighting a historical polyploidy event and subsequent genetic bottlenecks. This species, which constitutes the majority of global coffee production, faces susceptibility to pests and diseases due to inbreeding and limited genetic diversity, restricting its cultivation to specific regions with favorable conditions.

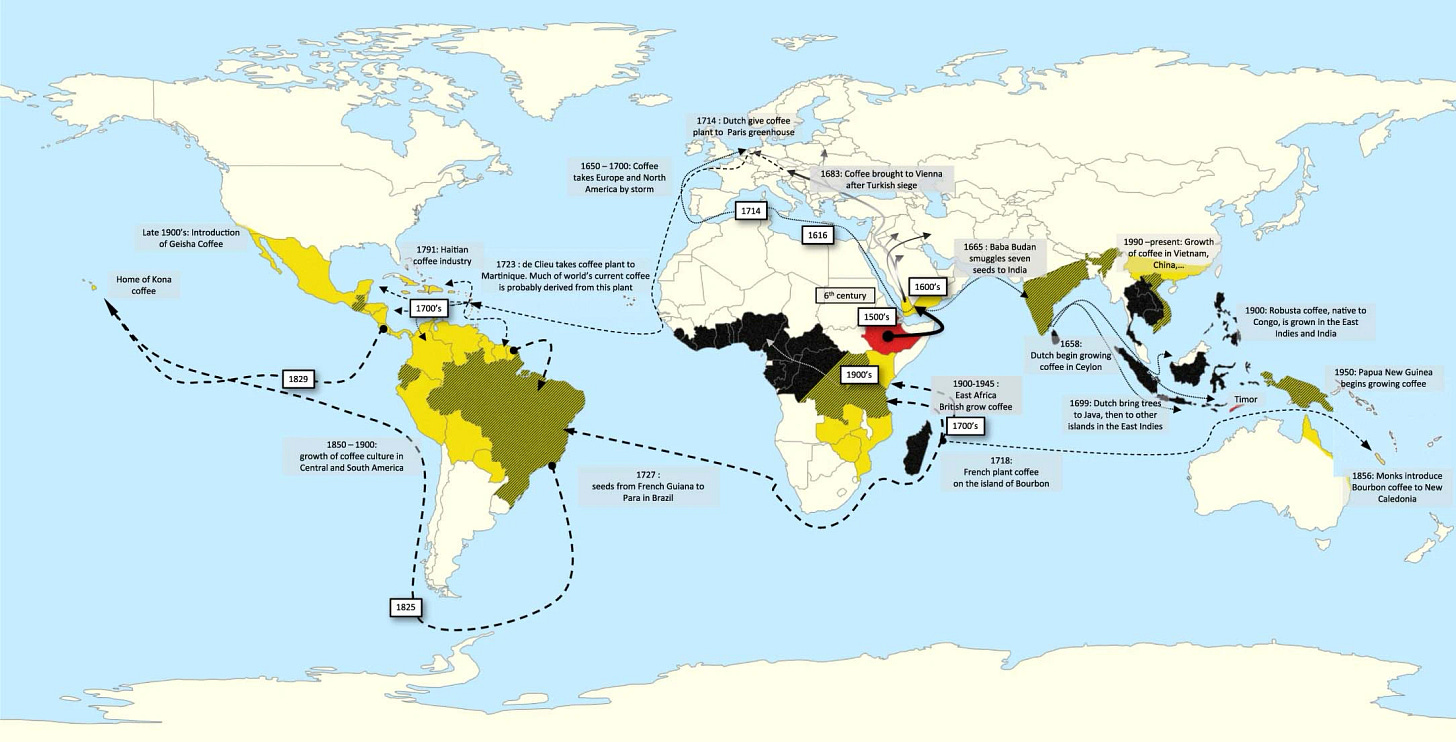

The world’s most popular coffee species, Coffea arabica, represents approximately 60% of coffee products worldwide. Due to a history of inbreeding and small population size, C. arabica is susceptible to many pests and diseases and can only be cultivated in a few places in the world where pathogen threats are lower, and climate conditions are more favorable.

A study was conducted on chromosome-level assemblies of C. arabica accession and modern representatives of its progenitors C. eugenioides and C. canephora. The study found evidence for a founding polyploidy event 350,000–610,000 years ago, followed by several pre-domestication bottlenecks, resulting in narrow genetic variation. A split between wild accessions and cultivar progenitors occurred ~30.5 thousand years ago, followed by a period of migration between the two populations. Analysis of modern varieties, including lines historically introgressed with C. canephora, highlights their breeding histories and loci that may contribute to pathogen resistance.

The findings have significant implications for the future of coffee cultivation, while laying the groundwork for future genomics-based breeding of C. arabica for improving pathogen resistance and climate change adaptation.

2. Phage predation, disease severity, and pathogen genetic diversity in cholera patients

(Science)

TL;DR: Bacteriophages, viruses that infect and replicate within bacteria, have shown potential as tools to combat bacterial infections, with a recent study in Bangladesh revealing correlations between the phage-to-bacteria ratio and disease severity in cholera patients.

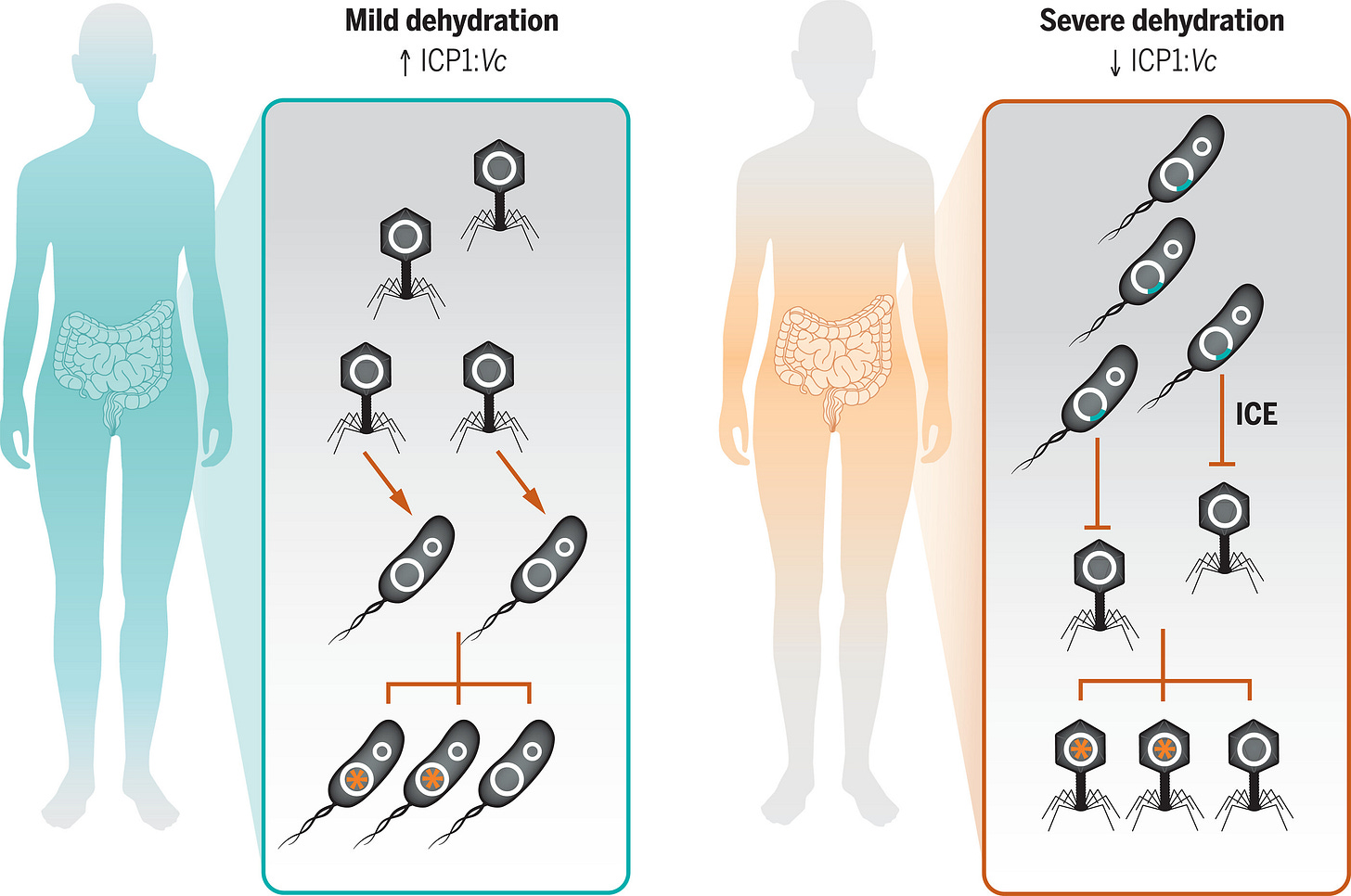

Bacteria (prey) can be hunted by bacteriophages (hunters), which are viruses that infect and replicate within bacteria. Phage therapy has also been proposed as a promising avenue to treat bacterial infections. However, the interaction between these two in real clinical settings, such as the human gut during infections, remain somewhat elusive. In a recent study of diarrheal infections in Bangladesh, focusing on cholera patients (caused by Vibrio cholerae infection), the researchers explored how factors such as phage prevalence, antibiotic resistance, and evolutionary dynamics shape disease severity.

The authors found that heightened ratios of phage:bacteria, in this case the virulent phage ICP1 and the bacterium V. cholerae, correlated with milder dehydration, while lower ratios were linked to moderate to severe dehydration. They also investigated the influence of integrative conjugative elements (ICEs), which encode phage resistance genes, on predation dynamics. Patients lacking detectable ICEs exhibited higher predator-to-prey ratios, termed "effective predation," while the presence of specific ICE variants was associated with resistance to ICP1.

The findings suggest that the phage-to-bacteria ratio could serve as a biomarker for disease severity in cholera patients, with ICP1 potentially exerting suppressive effects on V. cholerae and mitigating disease severity. These findings underscore the imperative of considering bacterial-phage coevolution in the development and application of phage-based therapies and diagnostics.

3. Airborne environmental DNA captures terrestrial vertebrate diversity in nature

(Molecular Ecology Resources)

TL;DR: Air sampling apparatus placed in a Danish mixed forest were able to capture airbourne eDNA (environmental DNA), detecting a plethora of birds, amphibians, fish and mammals. This research demonstrates the potential for using airborne eDNA monitoring for high-resolution and non-invasive monitoring of biodiversity.

The current biodiversity and climate crises have highlighted the need for efficient tools to monitor terrestrial ecosystems. A recent study demonstrated the use of airborne environmental DNA (eDNA) analyses as a novel method for detecting terrestrial vertebrate communities in nature. Environmental DNA refers to genetic material obtained directly from environmental samples (such as soil, seawater, or air) without any obvious signs of biological source material.

In this study, over 100 airborne eDNA samples were collected over three days in a mixed forest in Denmark, yielding 64 unique taxa comprised primarily of birds, but also mammals, fish, and amphibians. Furthermore, the method's detected taxa represented around a quarter of the terrestrial vertebrates that occur in the overall area. The study also provided evidence for the spatial movement and temporal patterns of airborne eDNA, and for the influence of weather conditions on vertebrate detection.

This research demonstrates the potential of airborne eDNA for high-resolution monitoring of biodiversity. The authors also note that this method could have massive implications for studies involving rare, shy or nocturnal animals, which are difficult to observe via traditional means, such as camera traps or audio recordings.

4. Effect of Isocaloric, Time-Restricted Eating on Body Weight in Adults With Obesity: A Randomized Controlled Trial

(Annals of Internal Medicine)

TL;DR: Researchers found that despite equal calorie intake, participants in a controlled study did not experience greater weight loss or improved glucose regulation with time-restricted feeding (TRE) compared to a usual eating pattern. This suggests that any benefits of TRE may be due to reduced calorie intake rather than meal timing.

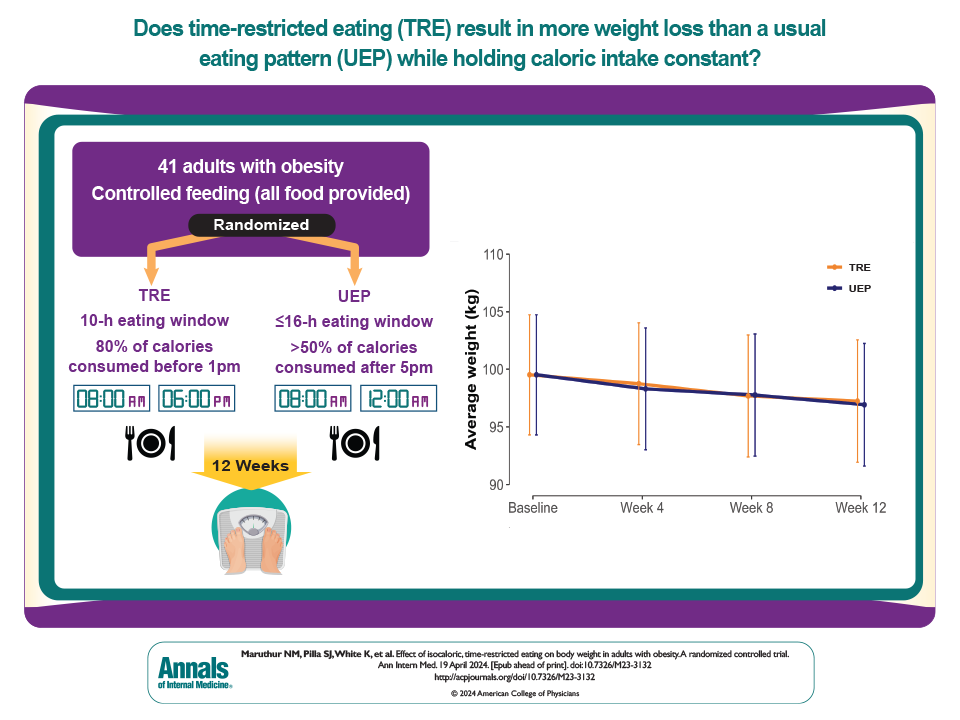

Recent research suggests that the timing of food intake may play a crucial role in weight management and metabolic health. Studies on rodents have shown that time-restricted feeding (TRE), which limits eating to specific windows each day, can improve weight, lipid profiles, and glucose regulation, even when calorie intake remains constant. Building on these findings, human trials have indicated potential benefits of TRE for weight loss and cardiometabolic outcomes, though many of these studies have lacked controlled feeding designs.

To address these gaps, a recent randomized controlled feeding study compared the effects of TRE versus a usual eating pattern (UEP) over 12 weeks in individuals with obesity and prediabetes or diet-controlled diabetes. Surprisingly, despite consuming the same amount of calories, participants following TRE did not experience greater weight loss or improvements in glycemic measures compared to those following UEP. These results suggest that any observed benefits of TRE on weight management in previous studies may be due to reduced calorie intake rather than specific effects of eating timing.

5. Differences in expression of male aggression between wild bonobos and chimpanzees

(Current Biology)

TL;DR: Bonobos are an endangered species of great apes that are amongst our closest cousins, sharing close to 99% of their DNA with humans. While originally known as the “make love not war” species, new research by Mouginot et al. show that there is more than meets the eye, as males were found to exert more aggressive behaviour than male chimpanzees.

Bonobos, previously misclassified as chimpanzees until cranial studies in the 1920s, have been the subject of several studies over the past decades; these studies established that bonobos exhibit less aggressive behavior than their neighboring species. They have even been characterized as the "make love not war" chimps, as males appear less dominant (with females dominating bonobo societies). In contrast, male chimpanzees have been found to be more prone to sexual coercion and susceptible to killing other members of their species.

However, new research by Mouginot et al. throws a monkey wrench in the “loving” bonobo theory. Using nearly 10,000 hours of focal follow data (wherein a researcher tracks a single animal and records all its social interactions over a period), they discovered that male bonobos exhibit higher levels of aggression towards male conspecifics. Furthermore, more aggressive males had greater reproductive success. While a similar observation was made in chimpanzees, the strategies appear to differ: whereas male chimpanzees rely heavily on forming coalitions, even engaging in border patrols with other males, male bonobos tend to operate more individualistically.

Other Stuff We’ve Been Reading (And Recommend!)

Avian Influenza A (H5N1) - United States of America: On 1 April 2024, the United States of America notified WHO of a laboratory-confirmed human case of avian influenza A(H5N1) detected in the state of Texas. (World Health Organization)

A glimpse of the next generation of AlphaFold: Progress update: Our latest AlphaFold model shows significantly improved accuracy and expands coverage beyond proteins to other biological molecules, including ligands. (Google DeepMind)

Jonathan Haidt Wants You to Take Away Your Kid's Phone: The social psychologist discusses the “great rewiring” of children’s brains, why social-media companies are to blame, and how to reverse course. (The New Yorker)

A world premiere: the living brain imaged with unrivaled clarity thanks to the world’s most powerful MRI machine (French Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission, CEA)

Discovering an Antimalarial Drug in Mao’s China: Chinese scientists discovered artemisinin in 1971 as part of a secret military project that merged Eastern and Western medicine. (Asimov Press)